Most people have been told this maxim at one point in their lives, usually by their mother or another older, wiser adult: breakfast is the most important meal of the day and skipping it can lead to weight gain, heart disease, and even diabetes. This claim makes sense rationally. If you eat a meal earlier in the day, the calories you intake will supply your body with fuel to burn off as you walk around and engage in other strenuous activities. However, many young people today typically skip this morning meal, not consuming anything besides coffee until lunchtime or later. This disparity got me to wondering how much of this claim is founded on empirical science, and how much is just an old wives’ tale. So I did a little research! It turns out there are a whole bunch of fluff pieces published by media outlets with catchy headlines like “How Long Should You Wait to Eat After Waking Up,” “What is the Best Time to Eat Breakfast, Lunch, and Dinner,” and the enigmatically titled “The Half-Hour Window”, that all make theoretical claims about what and when your ideal eating habits should be. And they are all exactly that: fluff. They are written based on ideas and theories, and not repeatable scientific experimentation, which is what science is based off.

So I began my search for scientific studies that address this dilemma. The first related study I came across was this one, in which over 50,000 members of Seventh-Day Adventist churches who were all at least 30 years of age had their BMI, or body mass index, measured and were asked to fill out tests to determine their demographic status, medical history, and general dietary habits. After a few years, the subjects had their BMIs tested again, with the changes observed in BMI over the elapsed time acting as the primary outcome variable. The independent variables in this experiment, or the variables that were thought to affect the primary outcome variable, were the number of meals the subjects consumed daily, whether or not subjects ate breakfast, the timing of their largest meal of the day, and the length of the largest break between meals or overnight fast. As we should expect if we listened to our mothers, the results generally followed common knowledge. Subjects who ate less than three meals per day experienced a reduction in BMI as compared to those who ate three, while those who ate more than three meals a day as a result of snacking generally experienced an increase in BMI. Subjects who ate a daily breakfast recorded a greater loss in BMI than those who skipped breakfast, and correspondingly, subjects whose largest meal of the day was breakfast experienced greater reductions in their BMIs as compared to those for whom the largest meal of the day came at dinner time. Subjects who ate their largest meal at lunch experienced a smaller but still notable decrease in BMI than those whose largest meal came at breakfast, showing that eating your largest meal of the day at morning correlates with the greatest degree of weight loss. One notable result this study shows is that eating your largest meal at dinner, as is most common in the United States, is in fact the least healthy way to spread out your eating. The most interesting result to me, however, was the effect of the length of subjects’ longest break between meals on their BMI. Subjects who had a long overnight fast (at least 18 hours) experienced a greater reduction in BMI than those who had only a medium overnight fast (12-17 hours), which would imply that the healthiest eating pattern would be to eat a large breakfast around say 8am, eat a smaller meal by 2, and then go without food until the following morning.

This study, while providing some very useful information on the topic at hand, did not come without its share of flaws in methodology. The experiment did not use a simple random sample, for starters, because the subjects used were all members of the Seventh-Day Adventist church. This type of sample is known as a convenience sample. All subjects were of course taken from the same religious sect, which could limit the diversity of the sample. For example, in doing a bit of digging into the methodology of this study, I discovered that the only racial groupings used to organize subjects were Black and Non-black, even though these groups included people of Caribbean origin as well as Asian and Latino people. Even though all eligible people were counted in this study, I can’t help but wonder the effects that these imprecise groupings could have had on the study’s results.

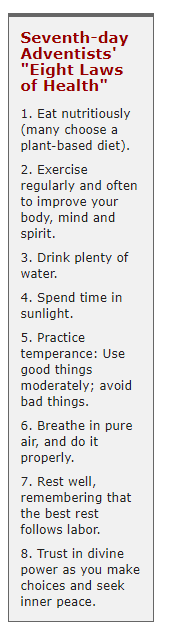

Another point of concern I have about the sample used in the study above involves the relative baseline health of the subjects. Members of the Seventh-Day Adventist church lead notoriously healthy lives, as is noted in this study where Dan Buettner traveled the world in search of the places where people lived the longest. In his study one of the places he visited was Linda Loma, California, where the mostly-Adventist citizens live to ages of over one hundred years at a much greater rate than in surrounding areas. The reasons that Adventists typically are so healthy and thus live so long can be seen in the “Eight Laws of Health”, taken from a oregonlive.com’s living section article that focuses on the superb health enjoyed by Seventh-Day Adventists, seen to the left. These Laws typify common Adventist beliefs, and though they are not universally seen as necessary for salvation they are followed to some extent by most members of the church. Since the subjects of the study in question live such healthy lives it makes taking the results and applying them to regular, not-so-healthy people a risky enterprise. Still, the relatively large sample size and the willingness of subjects to adapt to these potentially healthy lifestyle choices make this study more applicable and useful than most.

Now that I had one good resource on which to base my claims, I set out to locate more research to support them. The first one I found was this ‘scientific statement’ published by the American Heart Association that reviews data found in a number of contemporary studies that deal with the effects that specific eating patterns have on your cardiovascular health. The statement, which was released at the end of January 2017, examines effects on your cardiovascular health caused by skipping breakfast, intermittent fasting, along with the timing and frequency of meal consumption. It first set out to define the parameters used, like defining breakfast as any meal consumed within two hours after waking up before delving into the data gathered from number of previous studies. The data surveyed shows a broad correlation between eating larger meals later in the day and negative effects on cardiometabolic health, as well as negative health effects that go along with irregular eating patterns and the consumption of heavier meals later in the day. One notable correlation that was not found was any significant relationship between meal frequency, assuming equivalent caloric intake, and weight loss or cardiovascular health. The study therefor concludes that altering the number of times per day you consume calories may not be very useful for encouraging weight loss or improving cardiometabolic risk factors. Now since this ‘statement’ covers a number of previous studies and uses all that data to form conclusions, the total sample size is large enough to make the findings thereof very significant and make this a very useful data point from which to form our conclusions.

At this point in my research, I have found a couple very useful studies that use humans as subjects. The next step is to find a study that uses mice or other animal subjects to confirm the results. The main benefit to using animal studies is the degree of control that is allowed over them. Most studies that use human subjects are largely observational, especially when they cover broad subjects like eating habits, because of ethical concerns. Fortunately for science, people feel much less ethical concern for nonhuman animals, and will gladly perform studies where they are able to control the animals’ actions to a great degree. Since the concept of ‘breakfast’ is ultimately a human construct, I searched for studies that looked at the benefits of time-restricted feeding, or in other words looked at benefits to be gained from limiting caloric intake to a certain window of time, to mimic the aforementioned ‘overnight fast’ that is common in humans. I was able to locate this study, which examined the effects of time-restricted feeding on mice of different obesity levels under diverse nutritional challenges. Basically they subjected different mice to alternate times of feeding under a high-fat diet, a high-fructose diet, as well as a high-fat-plus-high-fructose diet and looked at the resulting changes in weight. Some mice were allowed to feed ad libitum, or at times of their choosing, while others were limited to time-restricted feeding, or were only allowed to eat in a 9-12 hour feeding window. As you can see in the graphic to the right, which was taken directly from the study, when mice were allowed to feed ad libitum they gained weight and became more obese, while when the mice were fed in a time-restricted window they generally lost weight. One thing this study did that has implications for humans is that they put some mice in a ‘weekly schedule’ grouping, where they stuck to a feeding window for five days and then switched to eating anytime for two days to mimic eating carefully during the workweek and then letting go over the weekend. This group of mice experienced less than half the weight gain of those were allowed ad libitum feeding, showing that time-restricted feeding can be very useful to prevent weight gain even when it is only practiced some of the time.

So in conclusion, the research I surveyed on the topic of the effects that consuming a breakfast meal can have on your health paints a clear picture: eating breakfast is just as important as your mom told you. We have seen multiple studies that address the question in human subjects that have arrived at the same conclusion, and while it is not practical to speak about breakfast in rodents we found some real benefits in consuming calories in a limited time or feeding window. So another result that you can take from this is that in addition to eating a balanced breakfast you should not consume calories late at night, as is shown by the importance of time-restricted feeding. That means you should avoid late dinners and midnight snacks if you want to achieve optimum levels of health.

2 Comments

Frodo T. Baggins

Concise and with evidence, makes for a good article. While it could use examples and analysis contrary to your conclusion, its length is a bit meaty to add that part of the discussion for those casual readers. But should they be inclined as to try eating alternatives, this piece could prompt them to do some research themselves.

joel

Yes, the website that I garnered one of the images from came to an alternate conclusion based on an experiment they had performed, but the sample size was like 36 subjects so far from statistically significant.

Love the username, btw 😉